If you don't know much about Justin Bieber's rise to superstardom, James Parker provides a good primer:

How did he do it? With YouTube, that’s how. Kissed in his cradle by the witch of the Web, Justin was throwing up little promo reels by the time he was 12. Singing a Brian McKnight song into the bathroom mirror. Or sitting on some municipal steps somewhere, busking mightily about the Lord: “You’re my God and my Fa-ther!” he bellows through the legs of passersby, the wooden body of his guitar reverberating with his shouts. ...

Bieber wasn’t from the Disney factory, and he didn’t have a show on Nickelodeon, so the marketing plan was skewed toward his already established constituency in social media: lots of Facebooking and YouTubing and sugary tweets to his millions-strong Twitter army.

Surface Encounters

Josh Pastner of Memphis Tigers gets new 5-year deal

![]() Memphis coach Josh Pastner receive a new five-year contract Tuesday.

Memphis coach Josh Pastner receive a new five-year contract Tuesday.

Surface Encounters

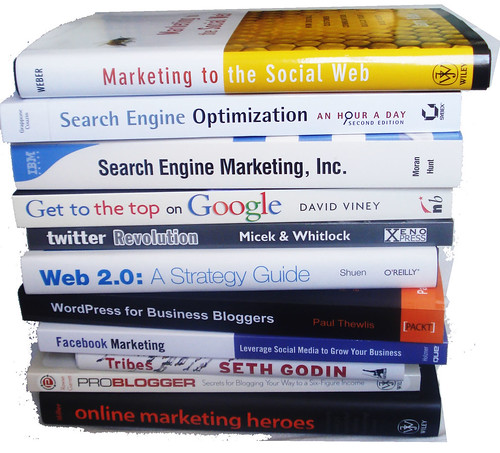

Small Business <b>News</b>: Social Media Brand

What is your social media brand? Do you have one? Sure, many small business owners and entrepreneurs are coming around to the enormous importance of social.

Surface Encounters

This Week in Credit Cards <b>News</b>: New Rules, More ATM Fees, End of <b>...</b>

Provided by LowCards.com New Rules Promote Smarter Use of Credit Cards The new consumer watchdog agency wants to help consumers understand the credit card offer they will receive before they apply for a credit card.

Surface Encounters

With the company’s future already clouded by Steve Jobs’ latest medical leave, the possibility of the iPad’s chief designer, Jonathan Ive, cashing out ups the uncertainty, Dan Lyons writes.

Is Apple losing its design guru?

When Apple CEO Steve Jobs announced in January that he would take a third medical leave, the biggest concern was the cloud of uncertainty that hovered over the company. Now that uncertainty has become an issue again, as rumors have started swirling that Apple might lose its chief designer, Jonathan Ive.

Apple's head designer Jonathan Ive poses for a portrait on January 27, 2010 in Cupertino, California. (Photo by Paul Harris / Newscom)

Reports in Ive’s native England suggest that the man who oversaw the design of the iPhone and iPad wants to spend more time in the U.K., putting him at odds with Apple’s board enough that he would consider leaving the company. Although Ive and Apple won’t comment, the scenario is plausible for two reasons: First, Ive is about to cash in options valued at $30 million that he was granted in 2008; and second, Ive has an especially close relationship with Jobs.

Whether Ive stays or goes, the brouhaha shows the challenges that Apple is increasingly likely to face given the questions about Jobs’ role in the coming months. One scenario being bandied about by Apple-watchers suggests Ive is making a power play to succeed Jobs; it seems just as likely, however, that he simply may not want to work at Apple if Jobs isn’t there.

Still others think the entire notion that Ive might leave is completely unfounded. But either way, the whole incident shows how the Jobs health situation is bringing more drama to a company that, until now, has been a model of tight-lipped discipline.

Apple’s products are famous for their sleek designs, and conventional wisdom holds that losing Ive would be a terrible blow to Apple—“Apple’s worst nightmare,” Britain’s Guardian called it. But the truth is, losing Ive may not be as big a deal as some Apple watchers think.

For one thing, Apple has loads of bench strength in every department, and because of its success it can attract just about anyone it wants.

“How much of this is Steve, how much is Jon, how much someone else? Steve always had an eye for design. The designer is only as good as the client,” says Jean-Louis Gassée.

For another, the real genius behind Apple’s designs might not be Ive—but rather Jobs.

That’s the educated guess of Jean-Louis Gassée, a former top executive at Apple and a longtime close watcher of the company who still has many connections there.

Gassée points out that Ive was already working at Apple when Jobs returned to the company in 1996. Ive joined the company in 1992, when Jobs was gone from the company, having been ousted by the board in 1985.

And before Jobs returned to Apple, Ive wasn’t exactly setting the world on fire. The first products that Ive designed under Jobs were the “Bondi Blue” iMac and the somewhat ugly iBook. Ive’s next products, the "desk lamp" Mac and the early metal laptops, were better looking, Gassée says.

Dirty Percent

Tuesday, 1 March 2011

It’s not hard to make the case that Apple’s new in-app subscription system offers numerous benefits to users, developers, and publishers. But whatever those benefits, they stem from the mere existence of these new subscription APIs. What’s controversial is the size of Apple’s cut: 30 percent.

No one is arguing that Apple shouldn’t get some cut of in-app purchases that go through iTunes. And, if Apple were taking a substantially smaller cut, there would be substantially fewer people objecting to Apple’s rules (that subscription-based publishing apps must use the system; that they can’t link to their external sign-up web page from within the app; and that they must offer in-app subscribers the same prices available outside the app).

The reasonable arguments against Apple’s policies seem to be:

Apple should be taking less, perhaps far less, than 30 percent.

Apple should not require subscription-based apps to use the in-app subscription APIs. If it’s a good deal for publishers, they’ll choose to use the system on their own.

Apple should not require price-matching from subscription offers outside the app. Publishers should be allowed to charge iOS users more money to cover Apple’s cut.

Apple should consider business models that simply can’t afford a 70/30 revenue split.

Let’s consider these in reverse order.

Apple Should Consider Business Models That Can’t Afford a 70/30 Revenue Split

Apple doesn’t give a damn about companies with business models that can’t afford a 70/30 split. Apple’s running a competitive business; competition is cold and hard. And who exactly can’t afford a 70/30 split? Middlemen. It’s not that Apple is opposed to middlemen — it’s that Apple wants to be the middleman. It’s difficult to expect them to be sympathetic to the plights of other middlemen.

Some of these apps and services that are left out might be ones that iOS users enjoy, though. This is the leading argument for how this new policy will in fact hurt users, and, as a result, Apple itself: it’ll drive good apps off the platform. Frequently mentioned examples: Netflix and Kindle. For all we know, though, Netflix may well be fine with this policy. Apple would only get a 30 percent cut of new subscriptions that go through the Netflix iOS app, and that might be a bounty Netflix can live with in exchange for more subscribers. Keep in mind, too, that Netflix and Apple seemingly get along well enough that Netflix is built into the Apple TV system software.

Kindle, and e-book platforms in general, are a different case. For one thing, Kindle doesn’t use subscriptions. Kindle offers purchases. Presumably, given Apple’s rejection of Sony’s e-book platform app last month, Apple is going to insist on the same rules for in-app purchases through apps like Kindle as they do for in-app subscriptions. If so, something’s got to give. The “agency model” through which e-books are sold requires the bookseller to give the publisher 70 percent of the sale price. So if the publisher gets 70 and Apple gets 30, that leaves a big fat nothing for Amazon, or Barnes & Noble, or Kobo, or anyone else selling books through native iOS apps — other than iBooks, of course.

But leaving aside the revenue split, there are technical limitations as well. The existing in-app purchasing system in iOS has a technical limit of 3,500 catalog items. I.e. any single app can offer no more than 3,500 items for in-app purchase. Amazon has hundreds of thousands of Kindle titles.

Something’s got to give here. I don’t know what, but there must be more news on this front coming soon. I don’t believe Apple wants to chase competing e-book platforms off the App Store.

Apple Should Not Require Price Matching

Why not allow developers and publishers to set their own prices for in-app subscriptions? One reason: Apple wants its customers to get the best price — and, to know that they’re getting the best price whenever they buy a subscription through an app. It’s a confidence in the brand thing: with Apple’s rules, users know they’re getting the best price, they know they’ll be able to unsubscribe easily, and they know their privacy is protected.

Credit card companies insist on similar rules: retailers pay a processing fee for every credit card transaction, but the credit card companies insist that these fees not be passed on to the customer. Customers pay the same price as they would if they used cash — which encourages them to use their credit card liberally. (Going further, many charge cards offer cash back on each purchase — they can do this because the cash-back percentage refunded to the customer is less than the transaction processing fee paid by the retailer.)

So the same-price rule is good for the user, and good for Apple. But Matt Drance argues that Apple could dissipate much of this subscription controversy by waiving this rule:

The requirement that IAP content be offered “at the same price

or less than it is offered outside the app,” combined with the

70/30 split, means developers must make less money off of iOS by

definition. They can’t price their IAP content higher to offset

the commission, nor can they price their own retail content lower.If I am interpreting this correctly, I can’t bring myself to see

it as reasonable. […] I think a great deal of this drama could

go away if Apple dropped section 11.13 while keeping section

11.14: Your prices on your store are your business; just don’t

be a jerk and advertise the difference all over ours.

And I agree with him. Yes, the same-price rule is good for users and for Apple, but waiving this rule wouldn’t be particularly bad for users or for Apple, either — and it would give publishers some freedom to experiment.

I suspect one reason Apple won’t budge is that their competitors — like Amazon — insist on best-price matching.

Apple Should Not Require Apps to Offer In-App Subscriptions

I’m sympathetic to this argument, too. “If you don’t like our terms, don’t use our subscription system.” But it has occurred to me that this entire in-app subscription debate mirrors the debate surrounding the App Store itself back in 2008 — that 30 percent was too large a cut for Apple to take, that it shouldn’t be mandatory, etc. The same way many developers wanted (and still want) a way to sell native iOS apps on their own, outside the App Store, many publishers now want a way to sell subscriptions on their own, outside the App Store.

The fact is, the App Store is an all-or-nothing affair. You play by Apple’s rules or you stick to web apps through Mobile Safari. This alternative is no different for periodical publishers than it was (and remains) for app developers in general. A lot of these demands boil down to a desire for more autonomy for native iOS app developers. Apple has never shown any interest in that.

There’s one striking difference between the subscription controversy today and the App Store controversy in 2008: with subscriptions, Apple is taking away the ability to do something that they previously allowed. There was never a supported way to install native apps for iOS before the App Store. Subscriptions sold outside the App Store, on the other hand, were allowed until last month.

Apple Should Be Taking Less, Possibly Far Less, Than 30 Percent

Another difference between the App Store itself and in-app subscriptions is that with apps, Apple hosts and serves the downloads. Apple covers the bandwidth, even for gargantuan gigabyte-or-larger 99-cent games. The OS handles installation.

With in-app subscriptions (and purchases), however, the app developer is responsible for hosting the content, and for writing the code to download, store, and manage it. So — one reasonable argument goes — given that Apple is doing less for subscription content than it does for apps (or for music and movies purchased through iTunes), Apple should take less of the money.

Taken further, the argument boils down to this: that for in-app subscriptions and purchases, Apple is serving only as a payment processer — and thus, a reasonable fee for transactions would be in the small single digits — 3, 4, maybe 5 percent, say. More or less something along the lines of what PayPal charges.

Apple, I think it’s clear, doesn’t see it this way. Apple sees the entire App Store, along with all native iOS apps, as an upscale, premium software store: owned, controlled, and managed like a physical shopping mall. Brick and mortar retailers don’t settle for a single-digit cut of retail prices; neither does the App Store.

Seth Godin argues that Apple’s 30 percent cut is too big to allow publishers to profit:

Except Apple has announced that they want to tax each subscription

made via the iPad at 30%. Yes, it’s a tax, because what it does is

dramatically decrease the incremental revenue from each

subscriber. An intelligent publisher only has two choices: raise

the price (punishing the reader and further cutting down

readership) or make it free and hope for mass (see my point above

about the infinite newsstand). When you make it free, it’s all

about the ads, and if you don’t reach tens or hundreds of

thousands of subscribers, you’ll fail.

Godin’s logic strikes me as questionable. For one thing, he freely switches between a newsstand metaphor (arguing, perhaps accurately, that the App Store is too large for publishers to gain attention from potential readers in the first place — you won’t read what you never notice) and the economics of subscriptions. But subscribers are the opposite of newsstand readers. Newsstand readers are buying a single copy, often on impulse. Subscribers are readers who are already hooked, and who know what they want. Put another way, the size of Apple’s cut of subscription revenue — whether it were higher or lower — has no bearing on the “attention at the newsstand” problem.

Second, the problem facing traditional publishers today is that circulation is falling. Newsstand sales and subscriptions are falling, under pressure from free-of-charge websites and other forms of digital content. The idea with Apple’s 70-30 revenue split is that developers and publishers can make it up in volume — that people aren’t just somewhat more willing to pay for content through iTunes than other online content stores, they are far more willing. The idea is that Apple has cracked a nut no one else1 has — they’ve created an ecosystem where hundreds of millions of people are willing to pay for digital content. Thus, potentially, publishers won’t just make more money keeping only 70 percent of subscription fees generated through iOS apps than they are now with 96 percent (or whatever they’re left with after payment processing fees) of subscription fees they’re selling on their own — they stand to make a lot more money.

I’m not guaranteeing or even predicting that it’s going to work out that way. I’m just saying that’s Apple’s proposition.

Godin’s assumption is that iOS in-app subscriptions won’t significantly increase the number of subscribers. If he’s right about that, then he’s right that Apple’s 30 percent cut will prove too expensive for publishers. But Apple’s bet is that in-app subscriptions can dramatically increase the number of subscribers. Consider the app landscape. Apple’s 30 percent cut didn’t drive the price of paid apps up — the nature of the App Store drove prices down. It’s a volume game.

The App Store itself proves that Apple might be right. Like with app sales, in-app subscriptions won’t work for every publication. But it could work for many. It really is possible to make it up in volume.

And if a 70-30 split for in-app subscription revenue doesn’t work, the price will come down. That’s how capitalism works. You choose a price and see how it goes. I’ll admit — when the App Store launched in 2008, I thought Apple’s 70-30 split was skewed too heavily in Apple’s favor. Not that it was wrong in any moral sense, but that it was wrong in a purely economic sense: that it might be more than developers would be willing to bear. Apple, clearly, has a better sense about what prices the market will bear than I (and, likely, you) do.

Competition vs. Anti-Competition

One last argument I’ve seen regarding these in-app subscription rules is that it’s further evidence of anti-competitive behavior from Apple. That makes sense only if you consider iOS to be the entire field of play. Apple, though, is competing at a higher level. They’re competing between platforms: iOS vs. Kindle/Amazon vs. Android/Google vs. Microsoft, and in some ways, vs. the free web. Why should publishers make an app rather than just a mobile web site? For happier customers and more money.

Sony has a platform for e-books. Amazon has a platform for e-books. Barnes & Noble has a platform for e-books. Apple has a platform for e-books. But Apple is the only one which allows its competitors to have apps on its devices. And Apple is the anti-competitive one? I’m no lawyer, but if the iTunes Music store hasn’t yet been deemed a monopoly with Apple selling 70+ percent of digital music players, then I doubt the App Store will be deemed a monopoly for a market where Apple has never been — and, according to market share trends, may never be — the top-selling smartphone maker, let alone own a majority of the market, let alone own more than a single-digit sliver of the phone market as a whole. As for ruthless profiteering, consider that Amazon, with their e-book publishing, originally took the fat end of a 70-30 revenue split with authors.

One question I’ve been asked by several DF readers who object to Apple’s new in-app subscription and purchasing policies goes like this: What if Microsoft did this with Windows, and, say, tried to require Apple to pay them 30 percent for every purchase made through iTunes on Windows? To that, I say: good luck with that. Microsoft couldn’t make such a change by fiat. The whole premise of Windows (and other personal computer systems) is that it is open to third-party software. Apple couldn’t just flip a switch and make Mac OS X a controlled app console system like iOS — they had to introduce the Mac App Store as an alternative to traditional software installation. If Microsoft introduced something similar to the Mac App Store for Windows, Apple would simply eschew it. If Microsoft were to mandate an iOS App Store-like total control policy for all Windows software, they’d have a revolt in their user base that would make Vista look like a success.

iOS isn’t and never was an open computer system. It’s a closed, controlled console system — more akin to Playstation or Wii or Xbox than to Mac OS X or Windows. It is, in Apple’s view, a privilege to have a native iOS app.

This is what galls some: Apple is doing this because they can, and no other company is in a position to do it. This is not a fear that in-app subscriptions will fail because Apple’s 30 percent slice is too high, but rather that in-app subscriptions will succeed despite Apple’s (in their minds) egregious profiteering. I.e. that charging what the market will bear is somehow unscrupulous. To the charge that Apple Inc. is a for-profit corporation run by staunch capitalists, I say, “Duh”.

If it works, Apple’s 30-percent take of in-app subscriptions will prove as objectionable in the long run as the App Store itself: not very.

Surface Encounters

Surface Encounters

Preview of Final Result

Resources

- PT Sans Bold – FontSquirrel

- Free App Icons for Developers – WebAppers

Step 1

Open Photoshop and create a new document that is 1200 x 1200 pixels, 72 dpi, and RGB Color. Fill the layer with white. (Ctrl+Backspace or Delete)

Step 2

Now create a rectangle for the header and fill it with a white-grey color, then use the colors on the image for the “Gradient Overlay”. Our search and logo will eventually be part of the header.

Step 3

Create a new rectangle above the previous one, with attributes as shown below. The following drop shadow effect creates a look of a 1 pixel stroke which does increase the look of that simple bar. Note: this step creates a horizontal line.

Step 4

Now add the “Gradient Overlay” layer style with the hex codes indicated.

Step 5

Add a white 1 pixel stroke. The following stroke of 1 pixel will divide the grey shadow effect. It’ll eventually work as a divider.

Step 6

Make one more rectangle in the middle-right zone, and fill it with white and add a 1 px stroke as indicated – it will be our search box.

Step 7

One more rectangle should be created and filled with blue. Set the inner shadow as indicated below, this will be our search button. This blue works great in combination with grey, white and light-grey. Blue will be the major contrasting color we use as we work through this template.

Step 8

Add the Gradient Overlay details to the button with the details from image.

Step 9

Add a 1 px stroke to the button with the color indicated. Take a look at the first and the final result of the button so you can see the difference all these details made.

Step 10

Now add this drop shadow effect for the text placed in the search box, using PT Sans Bold. This will be the final step in creating your search button. You may want to try other fonts, but the PT Sans Bold is really good for this small button.

Step 11

Make another fill under the header section, this will be the navigation area. Here we will place the navigation links of our template.

Step 12

Write your navigation links using a dark-grey color, then add a white “drop shadow” effect. The effect used for the navigation links is the same used for the search button.

Step 13

With 1px vertical line, make divisions between each links. The lines should be black and will really increase the beauty of the navigation area.

Step 14

Over the home section, make a fill with the blue and then add a Gradient Overlay style as indicated.

Step 15

Copy the Home link, this time color it white and add a drop shadow effect.

Step 16

Create a big, grey zone under the navigation, it should be about 30% of the layout. This will be the background for the featured area.

Step 17

Now create a big, white rectangle and add some shadow with the details shown. A big stock image, a big headline and some text with another great button will be added.

Step 18

Add a any dummy image you want to that featured area. Be sure it covers more than 80% of the area. The one I chose is from a stock website.

Step 19

Add some text to it, use the PT SANS Bold font and make the font big.

Step 20

The remaining area should be filled with grey, in it we’ll place some text. This is really a secondary area which describes the image, the services, the company itself, or whatever you’d like.

Step 21

Place some blue-colored text which will be the title of the information below. Use the details in the image for Drop Shadow style.

Step 22

Add some dummy text. This could be some important information or whatever you’d like.

Step 23

Create another grey area under the featured zone, where we will add some text and icons later. Add the details as stated on the image. Mostly, the icons will promote the services offered by the company behind the website.

Step 24

Continue by adding a Gradient Overlay style for the last rectangle we have created in the anterior steps.

Step 25

Now we are adding titles and icons, as well as some divisions. The icons can be found in the resource list at the beginning of the tutorial. Be sure to choose your icons and text thoughtfully.

Step 26

At the border of both zones, create a small circle and fill it with dark brown color. Add some inner shadow as stated on the image.

Step 27

Continue by adding a drop shadow layer style. It is another small detail, but it really makes that button zone minimalistic, nice-looking and well designed.

Step 28

To finish, add a Gradient Overlay effect.

Step 29

By using the Custom Shape Tool (U), create an arrow in both circles. Now add the details shown on the screenshot.

Step 30

Continue by adding some Color Overlay for the arrow. It should also be a blue color because otherwise, it will not fit the contrast and the colors used on the whole template.

Step 31

Add a video screenshot in the free space and place a title for it. For this template, I have used a simple screenshot of a YouTube widget.

Step 32

Add the text “Product Highlights” and “Case Studies.” Let the text under the “Product Highlights” be links so you could showcase some friends’ websites or resources you admire/promote.

Step 33

Finish it by creating another form for e-mails, place all kind of other information, and whatever you’d like.

Step 34

Don’t forget to make a relevant/small footer for our template. If you have paid attention, you should know how to create the same effect as below.

All done! If you have questions or suggestions, feel free to drop a comment. I hope you enjoyed this whole tutorial!

Surface Encounters

<b>News</b> FAIL - Epic Fail Funny Videos and Funny Pictures

Fox News is hard right heroine. They love pushing stories, even with only an ounce of truth and a pound of spin, to their audience. However, it is basically the only opposition voice people on the far right have besides talk radio. ...

Surface Encounters

Surface Encounters

Surface Encounters

FOCUS: Courageous workers at troubled nuclear plant endure tough <b>...</b>

Each of the employees of Tokyo Electric Power Co. and other workers engaged in containing damage at the stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is given 30 survival food crackers and a 180 milliliter pack of vegetable juice for ...

Surface Encounters